Our approach

Exclusive access to high-yield opportunities

Gain access to institutional-grade investments typically reserved for large institutions and family offices.

Customizable investment structures

Our flexible investment options allow investors to tailor their portfolios to align with their financial goals.

Proven expertise

and

leadership

With decades of experience in alternative investments, our leadership team strategically manages assets to maximize returns while mitigating risks.

Strong

governance

We employ a disciplined, data-driven investment process with rigorous due diligence, proactive monitoring, and strategic oversight to safeguard investor capital.

Diversified,

resilient portfolio

By investing across multiple asset classes and geographies, we minimize volatility and provide a stable foundation for long-term wealth generation.

Investor-centric

approach

Our commitment to investor education, transparency, and engagement ensures that every investor is well-informed, supported, and empowered in their financial journey.

A different kind of beginning

Born in crisis, Jeff Ballard raised $800K in private capital post 9/11.

Built on direct partnerships

Driven by investors, not Wall Street.

Built on direct partnerships

Driven by investors, not Wall Street.

Built on direct partnerships

Driven by investors, not Wall Street.

Built on direct partnerships

Driven by investors, not Wall Street.

Our offerings are engineered to align with your financial goals

Bespoke offerings for predictable income and tax-efficient growth

The Flex Fund

Designed for passive income seekers, this private credit offering provides fixed annual returns between 9.5% and 13%, customizable distribution frequencies... (monthly, quarterly, annually, or compounding), and flexible investment terms from...

The Legacy Funds

Built for compounding and capital growth, these long-term offerings target 11%–13% annual fixed returns with and additional 3% targeted equity upside starting in year three. Investors can compound tax-deferred earnings for up to 10 years or exit early with structured...

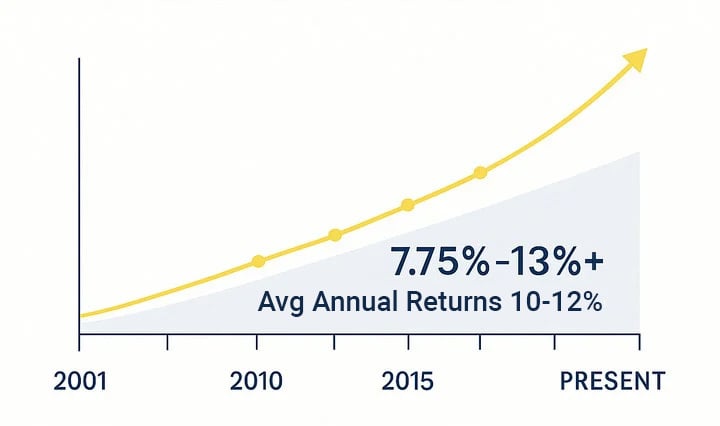

24 years. No investor capital losses.

Our track record

Since our inception in 2001, Ballard Global has never lost investor capital. We’ve launched over a dozen funds, each with a disciplined, risk-managed structure and consistent returns.

Steady, consistent returns averaging 10-12% annually through structured private equity and credit offerings.

Our performance is not hypothetical, it’s historical and consistent

Trusted by professionals. Chosen by families.

I have found Ballard to be attentive and helpful. They respond quickly to my questions and guide me through the issues I find difficult or confusing. I sleep better at night knowing that I have Ballard Global as an ally I can trust.

-D.M.

Retired Physician

Ballard Global has truly exemplified both professional excellence and a family - investment culture. My immediate and extended family, along with friends, are pleased with the returns we've received and the overall experience.

- R.G.

Customer Success Lead, Microsoft

- M.F.

Physician

- J.Y.

Dentist